A New Book! (The Fear & Trembling Stage)

And other things I've only been talking about in-person lately

Grappling. Have you ever thought about what it really means to grapple, what makes it such a helpful, tangible word? It means a “hand-to-hand struggle” or “a contest for mastery.” It makes me think of the grappling hooks that Batman and others use to reach up for some high destination, get a grip on it, and then bring themselves to it.

And isn’t that what we do when we set out on a new writing or thought project? We have some overarching question we are wrestling with inside, and we are reaching, reaching, reaching for some understanding that, especially at first, feels entirely out of reach. We wrangle, rant, roll things around in our heads, grappling and grappling until the ideas begin to take some shape that can be put to paper. (My brain is sweating just from describing it.)

Like so much of our language, part of what makes the word grapple great is that is based in an embodied metaphor. We intuitively know what it feels like to wrestle with an idea in our minds, but we reach for a physical metaphor to describe it. It feels like grappling.

Despite all the time we spend on disembodied online communication—and despite the phrases we use that compare us to machines—we are still embodied human beings. We intuitively know what it feels like to be in a body, and so we use the language of the body to describe even what’s going on in our minds and with our souls. And so does Scripture.

“For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood…” (Eph. 6:12).

“We are the clay, and you are our potter; we are all the work of your hand” (Isa. 64:8).

“And he put all things under his feet and gave him as head over all things to the church…” (Eph. 1:22).

God is the master of the embodied metaphor, because he made human bodies to mirror what is true about him and about the world. He gave us words and the Word—all of them rich with body references that help describe our reality. And then, he took it a step further when . . .

“The Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14).

“If you take the biblical metaphors seriously,” author Rebecca McLaughlin said, “so much of the fabric of our lives is actually an embodied metaphor to help us get a glimpse of God’s love and God’s glory.”

That’s a glimpse I don’t want to miss. Like all of creation, our bodies reflect and communicate something of what is true about God and about us. They tell us we are needy, and he is abundantly resourced. They cause us to seek after beauty, and he is its source and culmination. They tell us we are desperate for rest, and he is the one who gives his beloved sleep.

For too long I have seen my body as in the way of what I’m trying to do for the Lord. But through grappling with these concepts—through doing the slow work of developing a better theology of the body—I am beginning to see my physical frame not as an impediment to be overcome or a product to be perfected but as a gift to be received and used for good. As a metaphor worthy of meditation.

What if God gave us bodies for a reason, and we’ve completely missed the point?

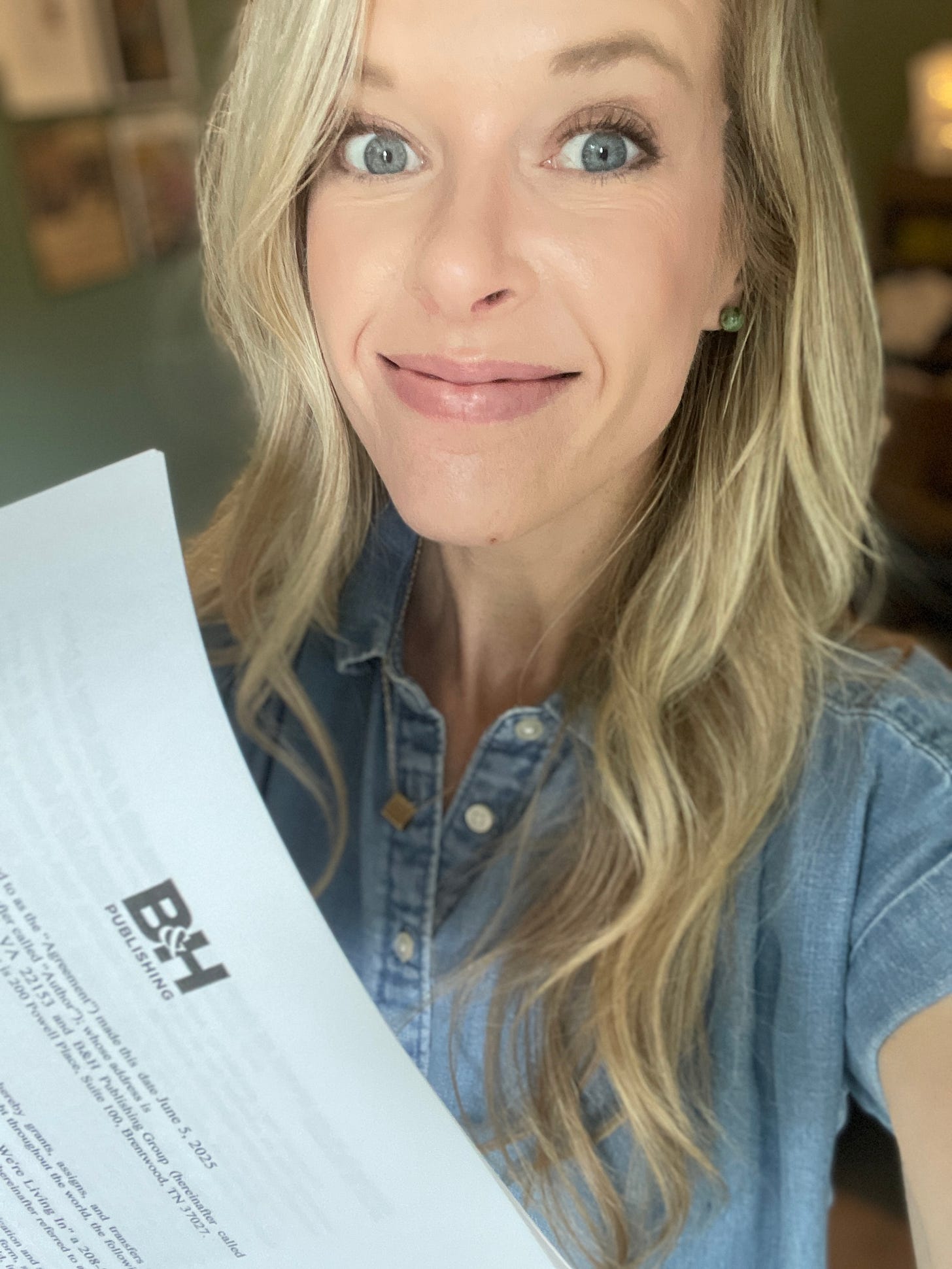

This is one of the questions at the center of my NEXT BOOK.

Yes, I’m writing another book!

Tentatively titled, The Skin We’re Living In: Why What We Believe About Our Bodies Matters (for B&H) this book will explore our urgent need for a functional and beautiful theology of the body.

We are living in an age that is prone to make both too much and too little of the bodies God has given us. On one hand, our culture and algorithms are constantly urging us to see the body as a machine-like tool to be optimized. We are always one click away from reaching some peak of physical performance, “wellness,” or productivity.

On the other hand, our cultural obsession with efficiency and technological advancement often leaves us living at odds with our bodies. We were created for good works in a body that limits us to a particular place at a particular time with a particular people. But technology would have us rise above all of that, outsourcing much of the work that was meant to form us while lulling us into a dopamine loop that discounts the necessity of bodily engagement.

We know this isn’t serving us well. We see it in all the statistics. But where do we—and particularly Christians—go from here?

In an overly image-oriented yet increasingly disembodied age, we need more than ever to renew our minds with what the Bible actually says the body is for. I believe that a better theology of the body is upstream of so many of our modern day issues. I believe that saturating ourselves with the goodness of the body will protect us more than anything from the false narratives our culture has to offer for our physical frames.

And I am praying that God would use this book to show us how our physical neediness points to a spiritual neediness that only an embodied Savior can satisfy. Because, it turns out, Jesus’ life in a body changes everything about our own.

Would you pray with me that God would be at work in and through this project? If there’s one thing I learned from writing We Shall All Be Changed, it’s that writing is a work I cannot and do not want to do on my own.

If you’d like to follow along as I work out these thoughts, with fear and trembling, you can subscribe to this newsletter.

What I’m Loving Lately✨

LISTEN 🎧 For more on the metaphors of the body and how rich they are in Scripture, listen to Jonathan Pennington on this episode of Culture Matters.

Scroll down to Media Coverage on this page for some recent podcast episodes I’ve been on. I always like to hear an author on a podcast before I buy their book.

WATCH 🎥 We have watched very little of anything so far this summer, but my husband and I did get a huge kick out of the first episode of Clarkson’s Farm on Amazon Prime. If you loved Top Gear, or if you love all things British television, British countryside, farming-adjacent and/or filled with failure, you’ll probably like this show. There is some language.

READ 📕 I am deep in the book The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains (2011; and this is when the library had it ready for me). It is making me feel both justified and terrified about my internet-addled brain’s ability to write another book. I read Deep Work before writing my first book, and this feels like a similar kick in the pants.

POETRY 📖: I found

’s encouragement toward gritty word choices in a recent piece for Mere Orthodoxy particularly inspiring.And go follow along for a new poetry series from my friend

, the first of which on God’s ‘overness’ had me weepy at the computer screen.

Oh friend, you’re a talented writer and your thoughts here are captivating. Thank you for sharing this with us and for doing this good work! Praying for you and with you!

Well done, excited for this!