I don’t know about you, but it’s the putting away of laundry that gets me.

My husband and I finish a day’s work, make a meal, clean up after said meal, get the children to bed and go upstairs already longing for our pillows, maybe for a few minutes with a book. And there’s the laundry basket, glaring at me. It is inevitably and perpetually filled to the brim with neat-ish piles of clothes I folded three, going on four days ago but just can’t conjure the energy to put away.

Why, I wonder, is it that I can keep the clothes moving through the machines, spend hours folding them and then just plumb run out of steam? Try as I might, I can’t seem to get them from the laundry basket to their respective places in the closet and drawers—even though I know it’s the quickest part of the entire laundry cycle.

But if it weren’t the laundry basket—which I do eventually empty only to immediately fill it with dirty clothes and start all over again—it would be something else.

“Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.”

You’ve heard of Newton’s Law, but have you heard of Parkinson’s Law? “Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion,” writer C. Northcote Parkinson reasoned in a 1955 article. He used the example that it can take an elderly person all morning to send one letter if that’s all she has to do, while a busy businessman could do it in a few minutes. (And I will counter his patronizing example with my own: I get a lot more done in my days as a mom than I did—or had to do—in earlier seasons of life.)

But I also see in this quote the reason why toasters and big tech haven’t actually given us more time to do the things we want to do: No matter how quickly we do the tasks, there will always be more. Oliver Burkeman writes in Four Thousand Weeks that this is the seedy underbelly of our productivity obsession. The more we do, the more the to-do list actually multiplies and expands.

Hence, the first-world laundry problem. I have washed and folded the laundry. Therefore, it must be put away (although, occasionally, my family manages just fine by plucking clean uniform shirts right out of the basket as needed). There are other examples: The more emails we send, the more emails we receive. The faster we work, the more work our boss sends us. And the tidier we aim to keep our house, the more likely we are to notice the one item that’s out of place, and then the other one.

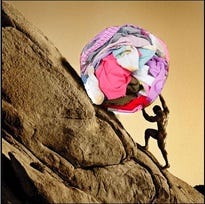

These tasks, Burkeman argues, are the rocks we, like Sisyphus, roll up the hills of modern life. Once we make it to the bottom of the laundry pile or the email inbox, it fills again. I, for one, don’t remember the last time I saw the bottom of either.

This truth was dawning on me this week after I stayed up too late finishing an article while attempting to cover at least parts of a public meeting that started one evening and lasted until morning the next day. After a good nap, I remembered something I’ve been learning and relearning in recent years: Though the treadmill of words to write and domestic work to do may never stop — I still can.

I can step right off and let it keep moving without me. The race to burn out is not one I want to win, so — even when I feel like I am — I am not losing ground. The machine isn’t actually moving. This is the odd comfort amid the constant whir of modern life: Even if it doesn’t stop — because it doesn’t stop — we can and we should. We are not machines; we are blessedly human.

I am learning in this season to reach for the off switch before I come to the utter end of myself and my reserves. Something about having more to do than I can possibly do on my own (see: book, job, kids) leaves me stopping mid-project far more than I thought I would. I know I can’t finish it all during this one work session. And I know I won’t be able to do much of anything else if I continually burn the midnight oil. So I stop.

There’s a comfort in constantly coming face-to-face with your limitations like this. Slowly, you learn to live within them. Coming to the end of my resources reminds me that I don’t have to do enough, be enough, have enough to do the things before me. I only have to return to the One who does.

This is the odd comfort amid the constant whir of modern life: Even if it doesn’t stop — because it doesn’t stop — we can and we should. We are not machines; we are blessedly human.

So what does this look like practically? On Wednesday night, at 8:30, it looked like calling it quits. I had more words I could put to the page, more laundry I could put away, but all the pouring out and putting up would not leave me with any less to do the following day. And I could feel in my bones that filling the space I saw unfurling before me would only leave me more depleted. So, instead of filling it, I received it.

I knew that, in my lack, I didn’t need more of something outside myself. I needed to rehearse God’s abundance, to sit under the sweet fount of it. I turned on slow piano music while I brushed my teeth, reminding myself that this wasn’t another task to complete but a time to refresh from yet another day of being human. “Oh, how abundant is your goodness,” I read again in Psalm 31, “which you have stored up for those who fear you and worked for those who take refuge in you, in the sight of the children of mankind!” (v. 19)

It is God who works to store up not just time and good work for us to do in it, but an abundance of his very goodness for us to receive. We find it, see it afresh, when — by practice or necessity — we pause to take refuge in Him. What does this goodness look like that is stored up for us even now?

The righteous, David writes in Psalm 36, “feast on the abundance of (God’s) house; (He) give(s) them drink from the river of (His) delights” (v. 8).

Stopping in the midst of the rush of right now has become, for me, a dress rehearsal for this feast, a putting on of what I know to be true beneath the current of life.

Pausing often feels like a defiant act of temperance in a world where time is the hottest commodity. And it is. But if God created all that I am and have and do — not out of any need, but out of His sheer abundance — then I am free to rest, to tarry in the midst of this limited time.

What’s been helping me take the time lately?

The Art in Bloom show on Discovery+, which features Helen Dealtry walking us through how she paints whimsical floral watercolors, has been sweet, laundry-folding medicine to me recently.

Naps. My college roommates will not believe that I take these now, usually on the Sabbath, but what a gift to receive. I struggle with deep sleep at night, but my watch confirms that I get almost all deep sleep when I give in to a midday rest.

Speaking of Sabbath and Temperance, I’ve heard beautiful podcasts on each recently. Emily P. Freeman’s interview of Ruth Haley Barton on why Sabbath is for everyone. And Joanna Meyer of the Faith & Work podcast interviewed Andy Crouch on Temperance in the work place. Would love to chat about either on Voxer!

What I’ve been writing.

Why you need a hard stop: How setting limits around work sessions teaches us and makes us better workers, for Women & Work.

Wrinkle Cream Can’t Redeem you: an article for The Gospel Coalition on the living hope story our changing faces have to tell us, if we let them.

What did women think of Jesus? A book review for the ERLC on Rebecca McLaughlin’s Jesus Through the Eyes of Women: How the First Female Disciples Help Us Know and Love the Lord.

Every woman works: There is no work-free option, for Women & Work.