“Everything is permissible for me,” but not everything is beneficial. “Everything is permissible for me,” but I will not be mastered by anything. (1 Cor. 6:12 CSB)

I was speaking to a group of young adults at a church in Wichita, Kansas, a couple weeks ago when I had something of a revelation. “Revelation” feels a little dramatic, but I looked up the definition, and it works: A “surprising and previously unknown fact… made known…” Yes. “Divine disclosure to humans of something relating to human existence or the world.” Maybe? Time will tell?

All I know is that I’d been stumbling around in the darkroom for weeks, waiting for an image to take shape under the red lights. And, suddenly, it did.

We were discussing the topic of embodiment and work. Really, I was thinking out loud, desperate for some feedback, particularly from younger folks, on ideas that have been gestating for some time.

We talked about how developing theologies of work and of the body can protect us from the ditches of beliefs that sound good but miss the mark. They can serve as corrective lenses of discernment, particularly when the messages coming at us contain a grain of truth.

Let’s take two major messages that seem woven into the ads, influencers and news updates running across our feeds:

1. That you are how you look. // That you can and should look or be better.

2. That you are what you accomplish. // That you can and should work faster/better/more efficiently.

Maybe one of these hits harder than the other. (Not sure? Your algorithm is.) But what is the common thread between these cultural beliefs on which so much of our economy is built? What is it about our human nature that seems so subject to overdoing it in these areas?

At it’s core, it’s the temptation to optimize ourselves. And it’s been made even more tempting lately by the perception that it can actually be achieved.

The possibility of avoiding aging and aches and pains… The possibility of avoiding unpleasant or “unnecessary” forms of work… These are both advents that technology has somewhat-suddenly enabled. And the sheer ubiquity of others’ adopting them makes it feel like they are inevitable adaptations to survive and thrive in a changing world.

But are they? And this is the question that came up as I talked with the young adults: Just because we can, does that mean we should? Just because we can now maintain an alarmingly youthful appearance (often at significant financial and mental costs), does that mean we should? Just because we can use ChatGPT and AI to write work emails and books and create art or Christian mom action figures, does that mean we should?

I realized while talking to this group that these are questions far too few of us are asking. These are areas of thought that are far more likely to be shaped by our algorithms than by what we say we believe.

These are areas of thought, then, ripe for discussion and desperate for discipleship. So let’s briefly begin to address them.

Your Long-Living Body of Beauty

You may think that whether to invest in an intense skincare routine or to download an AI app are theologically neutral choices—that they are areas so gray there may not be black and white options. And, by all means, let’s not reach for legalistic rules to keep our hearts in line when it comes to these topics. That has never served the church well, and it will not now. But let us also not opt out of making hard choices simply because the culture around us is keen to make them for us.

Perhaps you might be inclined to say what Paul anticipated the Philippians would say in response to his tough-love letter: “I am allowed to do anything,” to which Paul responds in 1 Cor. 6:12 (NLT), “But not everything is good for you. And even though ‘I am allowed to do anything,’ I must not become a slave to anything.”

Paul was dealing with food and sex, and Christian freedom. And he found a way, on those topics, to uphold that freedom while also holding out the goodness for which these Christians were made. They “were made for the Lord, and the Lord cares about our bodies” (v. 13 NLT).

So we have to ask ourselves: Does eager and unquestioning acceptance of new technologies by Christians stem from a thoughtful engagement with the pros and cons, or rather from a weak theology of what our bodies, our beauty and our technological tools are really for?

If the body is only a showpiece that exists to achieve and maintain the peak of its beauty and fitness, then every technology and expense can and should be used to that end. But if the body was made by God to glorify him and enjoy him forever, then physical beauty is just one small means to that end. And it is one to be held in tension with the formation and grace that comes with age. It is not, then, to be clung to at the exclusion of the good works on which we are called to spend our time and resources.

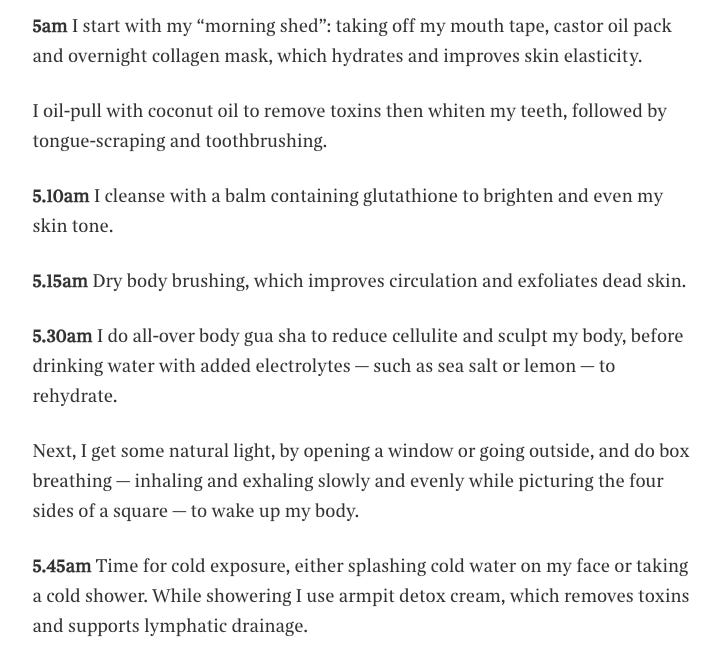

If you’re wondering at this point why and how I came to this topic, it’s this: Watch someone receive a deadly diagnosis that reveals how limited all our lives are and then see if they spend their days like this. Skim some of the “extreme daily routines” of the people who are leading the push for us to optimize our bodies’ beauty and longevity. We may not be able to definitively say where the line is—when the good things become idolatry—but we intuitively know there is one. Lord, help us see when we’re crossing it.

“All things are lawful for me,” Paul reminds the Corinthians (1 Cor. 6:12 ESV). “But I will not be dominated by anything.”

Your Body of Work

Likewise, if the body was made as God’s workmanship (poiēma) created for good works (Eph. 2:10), then getting that work done as quickly and effortlessly as possible isn’t exactly the goal. In fact, making it the goal could cause us to outsource the very work for which we were created.

“Okay,” I hear you saying, “but I only outsource menial tasks to AI.” Sure, and I really would love to sit across from you and discuss where the line may be. But here’s a question to grapple with meanwhile: What if those menial tasks were intended, as much as the “big” ones, to form you? What if seeking comfort and ease at all costs is antithetical to your formation as a Christian, as a human?

Of course, that argument can be taken too far. It is not necessarily wisdom to go back to doing laundry by hand simply to be formed by it. Technological tools can be great gifts that aide in the flourishing of humanity and the focusing of human effort on the greatest common good. But, be honest, is that what you’re using it for?

If I let AI write all my emails, I don’t have to feel the utterly human discomfort of, “But how do I communicate this clearly?” Perhaps outsourcing this menial task frees up extra time for me. But what do I do with it? And what is it costing me meanwhile?

Will I be more or less prepared for the hard, in-person conversation with a friend for not having written those uncomfortable emails? Or, over time, could I be so formed by the ease of online and assisted communication that I opt again and again for online over the effort and discomfort of being in-person?

This is not even to mention the very real environmental implications of powering AI, which I’ve seen firsthand in my reporting as a journalist. The land, power and water demands of this industry are so astronomical that they are difficult for our brains to truly compute.

Where I live in Northern Virginia—the global epicenter of the data centers that enable AI and every other online transaction—there are real, human impacts. (This new, 15-minute Bloomberg documentary does a great job of depicting it.) There are data centers with tractor-trailer-sized backup diesel generators (which emit harmful pollutants during regular testing for emergency use) being built next to high school football fields.

These dystopian-looking data centers are now seemingly built anywhere space is available near high-powered transmission lines, next to homes and schools and on green spaces formerly preserved to protect drinking water. The money fueling these projects makes them nearly impossible for local boards to deny. And behind it all is a growing sense that it’s inevitable anyway, that no one person can really stop the wave of change.

That may very well be true. When I was interviewing a “cloud anthropologist” for one of these stories, I asked him if forgoing a ring doorbell, for example, makes a dent in the data center deluge. He said no. Individual consumer choices cannot, on their own, turn the tide. A similar story has played out with the global proliferation of plastics and the irresistible ease they provide, which has now led to microplastics being found everywhere, including inside our own brains.

But none of this means that what the individual does or thinks does not matter. And that is especially true for the Christian who is accountable not to the mores of a digitized age but to God. Christians still have a say in how these waves of change hit and motivate and shape their own souls. But we are not saying much about it.

In the face of all of this, what can we do? Where do we start?

Maybe we can start small, as perhaps embodied people, limited to one space and place at a time, always should. As Christ in a body did. Maybe we can practice something that may feel like a drop in the bucket—an infinitesimal bulwark against the tsunami of change—but an action that has the power to transform first the person who practices it: Moderation.

We can choose to age wisely and, if necessary, bravely in an age that calls it optional. We can engage well in the hard work of writing and art and even meal planning, despite technology telling us we no longer have to. This technology may be in some sense inevitable, but going against your conscience never is.

The call is still to thoughtfully engage with this world in a way that acknowledges our utter dependence on God while promoting human flourishing. Aging… working… these are not things we can do on our own. Technology won’t save us from them. And, since God’s will is not only to save you but also “your sanctification” (1 Thess. 4:3), I’m willing to bet he’s more likely to shape us through things like aging and work than to save us from them.

p.s. If it seems like I’ve started a conversation here that can really only be addressed fully in book form… then stay tuned. 🧡

You had me at AI action figures. Can they go away maybe? I beg of people... 😊